Understanding Swift's Collection protocols

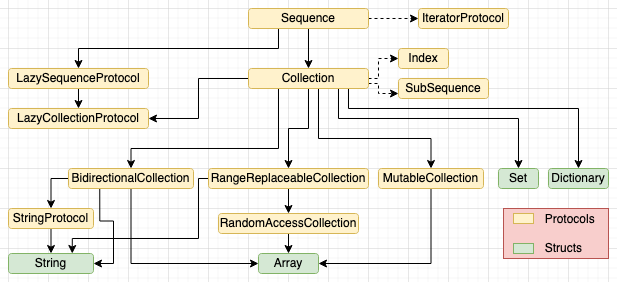

If there’s one aspect of Swift I avoided learning for the longest time, it would be the whole family of Collection types. The main reason is that the concrete implementations provided in the standard library - Arrays, Sets and Dictionaries - work fine for 99% of use cases. The other, more important reason - there’s just too many damn protocols!

Too many damn protocols!

Not to mention that Swift 5.5. introduced a whole new family of AsyncSequence based protocols, which we will not be touching in this post. Let’s try to figure what each of these protocols do, and why we need so many of them in the first place. We will do so by looking at each protocol starting from Sequence and moving down the tree.

IteratorProtocol

A type that supplies the values of a Sequence one at a time. This protocol is tightly linked with the Sequence protocol which we will see in some time. Sequences provide access to their elements by creating an iterator, which keeps track of its iteration process and returns one element at a time as it advances through the sequence. The protocol definition looks like this :

public protocol IteratorProtocol {

associatedtype Element

mutating func next() -> Element?

}A single method called next() that returns either next element or nil. It is marked mutating to give implementers a chance to update their internal state in preparation of next call to next(). If implementation does not return nil, iterators can keep producing values infinitely. We rarely need to create iterators directly, since sequences provide a more idiomatic approach for traversing sequences in Swift. Still, let’s create a concrete iterator to see how it works.

struct DoublingIterator: IteratorProtocol {

var value: Int

var limit: Int? = nil

mutating func next() -> Int? {

if let l = limit, value > l {

return nil

} else {

let current = value

value *= 2

return current

}

}

}

var doublingIterator = DoublingIterator(value: 1, limit: 1024)

while let value = doublingIterator.next() {

print(value)

}A simple iterator that doubles it’s value each time next() is called. If we omit the limit parameter in constructor, the iterator will keep doubling values forever.

Sequence

A type that provides sequential, iterated access to its elements. A sequence is a list of values that we can step through one at a time. While seemingly simple, this capability gives us access to a large number of operations that we can perform on any sequence. The Sequence protocol provides default implementations for many of these common operations. Before looking at these operations, let’s look at the protocol definition -

public protocol Sequence {

associatedtype Element

associatedtype Iterator: IteratorProtocol where Iterator.Element == Element

func makeIterator() -> some IteratorProtocol

}Sequence vends an Iterator via it’s makeIterator() method and the associatedtype requirements ensure that Element types of the iterator and sequence match. Let’s create a concrete DoublingSequence using our DoublingIterator -

struct DoublingSequence: Sequence {

var value: Int

var limit: Int? = nil

func makeIterator() -> DoublingIterator {

DoublingIterator(value: value, limit: limit)

}

}

let doubler = DoublingSequence(value: 1, limit: 1024)

for value in doubler {

print(value)

}

print(doubler.contains { $0 == 512 }) // true

print(doubler.reduce(0, +)) // 2047Just by conforming to Sequence, our concrete type has gained the ability to be used in for-in loops and useful operations like map, filter, reduce etc. Sequence also gives us methods like dropFirst(_:), dropLast(_:) etc. However, at Sequence level, the implementations of these methods are bound by the constraint of iterating over elements one at a time. This reflects in their time complexities - with dropFirst(_:) being O(k) where k is number of elements to drop, and dropLast(_:) being O(n) where n is total number of elements in sequence. dropLast(_:), unlike dropFirst(_:), requires the sequence to be finite.

There are a couple of things to be aware of while using Sequences -

- Sequence makes no guarantees about multiple iterations producing desired results. It is up to the implementing type to decide how to handle iterating over an sequence that has already been iterated over once.

- Sequence should provide it’s iterator in O(1). It makes no other requirements about element access. So methods that traverse a sequence should be considered O(n) unless documented otherwise.

Given an element, Sequence lets us move to next element. To be able to move to any element (no guarantees of the move being constant time though), we need Collection.

Collection

A sequence whose elements can be traversed multiple times, nondestructively, and accessed by an indexed subscript. When we use arrays, dictionaries or sets, we benefit from the operations that the Collection protocol declares and implements. In addition to the operations that collections inherit from the Sequence protocol, we gain access to methods that depend on accessing an element at a specific position in a collection. The minimum protocol definition for Collection looks like this -

protocol Collection: Sequence {

associatedtype Index: Comparable

var startIndex: Index { get }

var endIndex: Index { get }

subscript(position: Index) -> Element { get }

func index(after i: Index) -> Index

}Due to the requirements of multiple traversal and access via indexed subscript, a Collection cannot compute it’s values lazily, nor can it be infinite. This is a departure from Sequences, which can use the current call to next() to update the internal state in preparation on next call. Also note that associatedtype Index is not a Int, but can be any type that conforms to Comparable.

To better understand Collection (and types that will follow later) let’s create a concrete Collection type called FunkyArray that behaves like an array, but instead of Ints, uses characters [A-Z] as indices. By it’s nature, FunkyArray can only store a maximum of 26 items, but we are not aiming for practicality here. We will gradually make our FunkyArray conform to more specific Collection types and see what functionality we unlock with each conformance.

struct FunkyArray<Element> {

private let start: Character = "A" // Start Index

private let end: Character = "[" // End Index. ASCII char after Z

private var internalArray = [Element]()

init<S: Collection>(_ elements: S) where S.Element == Element {

let maxElements = charToInt(end) - charToInt(start)

precondition(elements.count <= maxElements, "FunkyArray can have max of \(maxElements) elements.")

elements.forEach { internalArray.append($0) }

}

/// Converts character index to int index.

/// A becomes 0, J becomes 10, Z becomes 25

private func charToInt(_ char: Character) -> Int {

Int(char.asciiValue! - start.asciiValue!)

}

/// Converts int index to character index.

/// 0 becomes A, 10 becomes J, 25 becomes Z

private func intToChar(_ int: Int) -> Character {

Character(UnicodeScalar(start.asciiValue! + UInt8(int)))

}

}In our FunkyArray implementation, we have used a regular array as backing store. We use ASCII codes to convert between Character and Int indices as necessary. Adding conformance to Collection is a simple affair -

extension FunkyArray: Collection {

var startIndex: Character { start }

var endIndex: Character { intToChar(internalArray.endIndex) }

subscript(position: Character) -> Element {

get {

let intIndex = charToInt(position)

return internalArray[intIndex]

}

}

func index(after i: Character) -> Character {

// precondition ensures index nevers goes past Z

precondition(i < end, "Index out of bounds")

return intToChar(charToInt(i) + 1)

}

}

var funkyArray = FunkyArray([1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32])

print(funkyArray["F"]) // 32

print(funkyArray.firstIndex { $0 > 30 } ?? "-") // F

print(funkyArray["G"]) // Fatal error: Index out of rangeUsing subscripts, we can access a single element in our FunkyArray, our even use a subscript range to access a bunch of Elements at once.

var funkyArray = FunkyArray([1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32])

let sub = funkyArray["B"..<"D"]

sub.forEach { print($0) } // 2 4If we inspect the type of sub, it will be Slice<FunkyArray<Int>>. Accessing a subrange of Collection, does not return a new Collection, but rather a SubSequence. Slice is a default implementation of SubSequence if the Collection does not provide it’s own implementation. SubSequence is a thin wrapper referencing the original collection, but with different start and end indices. This makes subsequencing extremely fast, but there are some gotchas to be aware of -

var funkyArray = FunkyArray([1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32])

let sub = funkyArray["B"..<"D"]

print(sub.startIndex) // B

print(sub.endIndex) // D

print(sub["A"]) // Fatal error: Out of bounds: index < startIndex

let sub2 = FunkyArray(sub)

print(sub2.startIndex) // A

print(sub2.endIndex) // C

print(sub2["A"]) // 2SubSequences share the indices of the backing Collection, and only update their own start and end indices. This means trying to access them using indices of original Collection can result in out of bounds error. As a general rule of thumb, even if the index types match, it is not a good idea to use indices from one Collection to access elements from another. The Swift compiler transparently creates a new copy of SubSequence whenever there’s a modification. This behaviour is known as Copy-on-Write and preserves the value semantics of Collections while also enabling fast subsequencing.

Conforming to Collection gives us access to firstIndex(where:), since this method internally uses our implementation of index(after:). However we don’t have the ability to find the last index satisfying given predicate. For that, we need to conform to BidirectionalCollection.

BidirectionalCollection

BidirectionalCollection supports backward as well as forward traversal. Bidirectional collections offer traversal backward from any valid index, not including a collection’s startIndex. Bidirectional collections can therefore offer additional operations, such as a last property that provides efficient access to the last element. In addition, bidirectional collections have more efficient implementations of some sequence and collection methods, such as reversed(). The protocol definition is simple -

protocol BidirectionalCollection: Collection {

func index(before i: Index) -> Index

}We just need to implement a method that gives an index immediately before passed index.

extension FunkyArray: BidirectionalCollection {

func index(before i: Character) -> Character {

// precondition ensures index nevers goes past A

precondition(i > start, "Index out of bounds")

return intToChar(charToInt(i) - 1)

}

}

print(funkyArray.last!) // 32

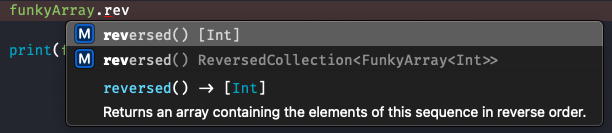

print(funkyArray.lastIndex { $0 < 5 } ?? "-") // CThe ability to traverse backwards enables BidirectionalCollection to refine the implementation of reversed() method. reversed() is originally implemented at Sequence level with return type as Array<Element>. At Sequence level, it has O(N) runtime as the algorithm has to eagerly read elements from start to end, much like you or I would do it if asked to implement reversed() in an interview. BidirectionalCollection implements reversed() in a way that does not read Sequence elements at all, but returns a new type called ReversedCollection that wraps the original Collection. ReversedCollection transparently converts it’s own indices into indices for base collection, and simply accesses elements from base collection as needed. Creating ReversedCollection has O(1) complexity.

Since the return type for Sequence implementation differs from the BidirectionalCollection’s return type, we can see two autocomplete prompts for reversed() in Xcode. We can select the one we want by explicitly declaring the type of variable supposed to hold the value of reversed().

Two implementations of reversed()

We can now move through our FunkyArray from both ends. But we can’t yet change the value at any given Index. That functionality is provided by MutableCollection.

MutableCollection

If we try to modify any value in FunkyArray using subscript, we will be greeted with a compile error. Collection only gives us subscript read access to it’s elements. To unlock write access, we need to conform to MutableCollection. Protocol definition is simple -

protocol MutableCollection: Collection {

subscript(position: Index) -> Element { get set }

}We need to update the subscript definition in our Collection to support both get and set. If you recall, Collection only mandated get. We can’t add just the set part of subscript definition in an extension, so we actually need to update the Collection extension of FunkyArray.

extension FunkyArray: MutableCollection {

var startIndex: Character { start }

var endIndex: Character { intToChar(internalArray.endIndex) }

subscript(position: Character) -> Element {

get {

let intIndex = charToInt(position)

return internalArray[intIndex]

}

set(newValue) {

let intIndex = charToInt(position)

internalArray[intIndex] = newValue

}

}

func index(after i: Character) -> Character {

// precondition ensures index nevers goes past Z

precondition(i < end, "Index out of bounds")

return intToChar(charToInt(i) + 1)

}

}

var funkyArray = FunkyArray([1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32])

funkyArray["F"] = 64

print(funkyArray) // 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 64MutableCollection seems like a simple addition, but it gives us access to useful methods like swapAt(_:_:) for swapping elements at two indices and reverse() for in-place reversal. One thing to be aware of while implementing MutableCollection is that subscript assignment should not change the length of the Collection itself. This is the reason why Strings don’t conform to MutableCollection. Replacing a Character with another using subscript can change the length of String as Character itself doesn’t have a fixed length. The length constraint is also the reason why MutableCollection doesn’t provide methods like remove(_:), append(_:), insert(_:at:) etc which we typically associate with the word “mutable”.

Remember how Collection enabled us to move to any element using Index, but made no guarantees of the move being constant time? RandomAccessCollection is the protocol which gives us this guarantee.

RandomAccessCollection

A collection that supports efficient random access index traversal. RandomAccessCollections can move indices any distance and measure the distance between indices in O(1) time. Therefore, the fundamental difference between random access and bidirectional collections is that operations that depend on index movement or distance measurement offer significantly improved efficiency. The protocol definition is as simple as it gets -

public protocol RandomAccessCollection: BidirectionalCollection

where SubSequence: RandomAccessCollection, Indices: RandomAccessCollection { }Besides requiring SubSequence and Indices types of BidirectionalCollection to themselves be RandomAccessCollections, it adds no requirements of it’s own. What good is a protocol that has no requirements, you ask? Well, the actual requirements of RandomAccessCollection - implementing the index(_:offsetBy:) and distance(from:to:) methods with O(1) efficiency - can’t be enforced at compile time. 1. Conformance to this protocol is based on trust - the compiler trusts that our implementations meet the time complexity requirements since it can’t verify them. Since our FunkyArray internally uses array which already conforms to RandomAccessCollection, we don’t need to provide refined implementations for any of the two methods.

extension FunkyArray: RandomAccessCollection { }Conforming to RandomAccessCollection doesn’t unlock a lot in terms of functionality, but it does improve performance of certain existing algorithms like dropFirst(_:), dropLast(_:), prefix(_:), suffix(_:) which become O(1) operations now. Most importantly, count property is guaranteed to be O(1) instead of (possibly) requiring iteration of an entire collection. If our RandomAccessCollection also conforms to MutableCollection, we gain access to in-place sort() and shuffle() methods as well.

Speaking of MutableCollections, our FunkyArray - despite being a mutable collection - still cannot do length changing operations like insert(_:at:). Such operations require conformance to RangeReplaceableCollection.

RangeReplaceableCollection

A collection that does what it says. RangeReplaceableCollection supports replacement of an arbitrary subrange of elements with elements of another collection. This sounds a bit like MutableCollection, but the key difference here is that the new collection need not have same length as the one being replaced. Protocol definition is simple -

protocol RangeReplaceableCollection: Collection {

init()

mutating func replaceSubrange<C>(_ subrange: Range<Index>, with newElements: C)

where C: Collection, C.Element == Element

}Conforming to the protocol is also simple2 -

extension FunkyArray: RangeReplaceableCollection {

init() {}

mutating func replaceSubrange<C>(_ subrange: Range<Character>, with newElements: C)

where C : Collection, Element == C.Element {

let firstIndex = charToInt(subrange.lowerBound) - charToInt(startIndex)

let lastIndex = charToInt(subrange.upperBound) - charToInt(startIndex)

internalArray.replaceSubrange(firstIndex..<lastIndex, with: newElements)

}

}

var funkyArray = FunkyArray([1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32])

funkyArray.append(contentsOf: [10, 20 ,30])

print(funkyArray) // 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 64, 10, 20, 30This single method unlocks a host of new functionality. We can insert a new collection at any index, accomplished by making index..<index as subrange. We can append a collection at the end, accomplished be inserting the collection at endIndex and remove all elements from collections, accomplished by simply calling the empty init.

Since RangeReplaceableCollections can modify the length of Collection, Strings can safely conform to it, unlike MutableCollection.

Dictionaries and Sets

Despite having a number of Collection protocols fine tuned for very specific constraints, things are far from perfect. Case in point being unordered collections like Sets and Dictionaries. Sets conform to Collection, which gives them access to methods like firstIndex(of:), subscript { get } etc. This method makes no sense for an unordered Collection like Set. But I guess the benefits of conforming to Collection outweighed having a few API inconsistencies. Majority of set operations are implemented in Set type directly, or in SetAlgebra type which sits outside the Collection protocols we discussed in this post.

Dictionaries conform to Collection as well. Based on the way you access a value using key as subscript, you would expect the Index to be of key’s type and Element to be of value’s type. However, dictionaries actually use an internal type for their Index and their Element type is a tuple (Key, Value). A look a Dictionary’s code shows that there are actually two subscripts, one based on the internal Index to satisfy Collection protocol requirements and another using Key which we are familiar with.

References

- harshil.net - Inspiration behind this post.

- Swift source code - Swift stdlib is surprisingly well commented and readable.

I wonder if there’s any compiler that can enforce runtime complexity at compile time… 🤔 ↩︎

A bug in Swift compiler enables us to conform to RangeReplaceableCollection without implementing any methods. This causes no compile time errors, but an infinite loop at runtime. This issue has been fixed and merged. Next public release of Swift will likely include this fix. ↩︎