Exploring Memory layout and Pointers in Swift

What is Memory?

Memory can be thought of a sequence of one or more bytes, with each byte addressable in some way. Computers today typically have three levels of memory, with each layer providing more storage space - but also slower access times - than the layer above

- CPU Registers - addressable directly by register names (R1, R2 etc).

- RAM - addressable by a memory address assigned to each byte stored in it.

- Disk - addressing depends on the filesystem being used.

In this post, we are mainly concerned with RAM memory since that is where all the structs and classes we define end up being stored at runtime.

If you were to pause execution of any running program and sample a chunk of memory, it might look something like this :

…0010101001011111101011001110001100000001…

A long stream of 0s and 1s that is undecipherable to us, but makes total sense to the computer. We normally group these in groups of eight called bytes.

| … | 00101010 | 01011111 | 10101100 | 11100011 | 00000001 | … |

|---|

1 byte can be represented using 2 hex digits. Assigning random addresses to this chunk gives us this visualization -

| … | 42 | 5F | AC | E3 | 01 | … |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| … | 100 | 101 | 102 | 103 | 104 | … |

Top row = Byte value, Bottom row = Address.

Looking at raw bytes like this tells you nothing about what the data actually means. The addresses above could be 5 bytes of an Int64, or an array of [Int8], or something else altogether. The program managing this chunk of memory has context on how to interpret this sequence of bytes.

Memory Layout of structs

Swift has an enum called MemoryLayout that provides information about a type’s size (in bytes) and layout in memory. Let’s define a struct with two properties and check it’s MemoryLayout -

struct TestStruct {

let integer: Int32

let boolean: Bool

}

print(MemoryLayout<TestStruct>.size) // prints 5

print(MemoryLayout<TestStruct>.alignment) // prints 4

print(MemoryLayout<TestStruct>.stride) // prints 8The size of struct is the sum of size of it’s individual properties. TestStruct has a Int32 property which takes 4 bytes and a Bool property which takes 1 byte. So the size of struct itself is 5 bytes.

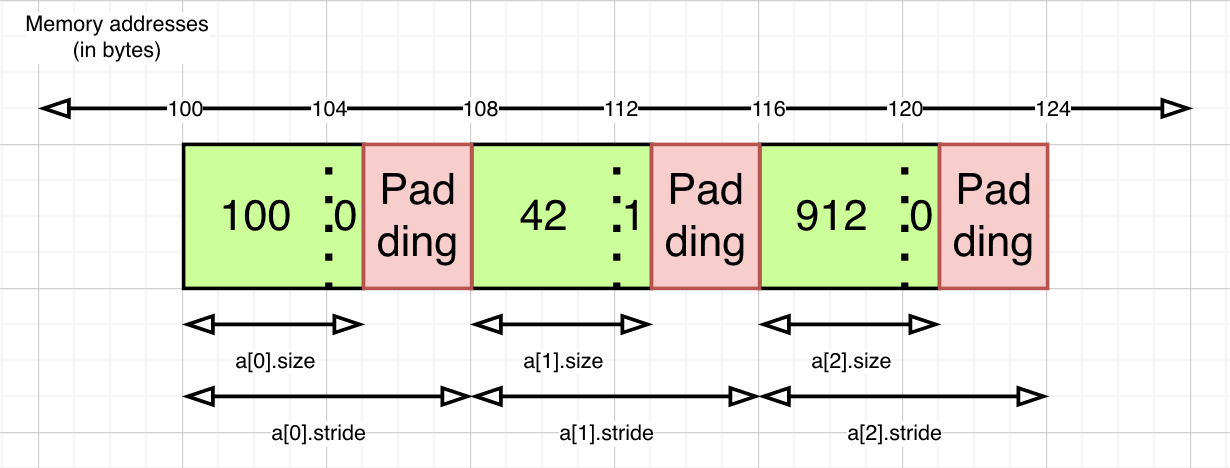

When multiples structs are placed sequentially in memory (like in an array), structs really like to placed at a standard distance from each other, padding the remaining bytes as necessary. This distance is known as alignment.

The actual memory footprint of a struct is a multiple of alignment, rather than size. This memory footprint is called stride.

Visually, multiple instances of TestStruct stored sequentially might look something like this in memory -

If you change integer property to be of type Int64 rather than Int32, the alignment of the struct would become 8 bytes. Consequently, it’s stride will also increase to be a multiple of alignment, i.e 16 bytes.

Pointer types in Swift

A pointer is nothing more than a memory address, which can be represented using a simple UInt. However, this simple representation is hard to work with since UInt doesn’t tell us anything about the thing being pointed at (a.k.a the pointee). Swift’s pointer types can either by typed (like int *, char * in C) or raw (void *). Further, they can be mutable (i.e allow changing the pointee) or immutable. Typed pointers are generic over a type T.

| - | Immutable | Mutable |

|---|---|---|

| Typed | UnsafePointer<T> | UnsafeMutablePointer<T> |

| Raw | UnsafeRawPointer | UnsafeMutableRawPointer |

Swift also provides buffer variants of the above four types. Buffer pointers denote a range of memory addresses rather than a single address and have collection methods like map, filter, reduce to make dealing with a chunk of contiguous memory easier.

| - | Immutable | Mutable |

|---|---|---|

| Typed | UnsafeBufferPointer<Element> | UnsafeMutableBufferPointer<Element> |

| Raw | UnsafeRawBufferPointer | UnsafeMutableRawBufferPointer |

Enough theory! Let’s see how to use these types in practice.

Pointer related APIs

There are very few instances when you actually need to create a pointer from scratch. More commonly, you will have an existing type whose pointer you need. Swift provides nice closure based APIs to access any type’s pointer. Let’s see how that looks -

let test = TestStruct(integer: 42, boolean: true)

withUnsafePointer(to: test) { (pointer) in

print(pointer) // 0x00007ffeeea402c0

print(pointer.pointee) // TestStruct(integer: 42, boolean: true)

}The global function withUnsafePointer() takes in a generic type T and a closure (UnsafePointer<T>) -> Result. You can do your pointer magic within the body of the closure and return any value you fancy. The closure provides a clean separation between safe and unsafe parts of your code. In the above code, you cannot change the value of test using it’s pointer. If we want to do that, we need to use the withUnsafeMutablePointer function instead -

var test = TestStruct(integer: 42, boolean: true)

withUnsafeMutablePointer(to: &test) { (mutablePointer) in

mutablePointer.pointee = TestStruct(integer: 10, boolean: false)

print(mutablePointer.pointee) // TestStruct(integer: 10, boolean: false)

}

print(test) // TestStruct(integer: 10, boolean: false)In C lingo, the first pointer instance you get inside the closure would be of type const TestStruct *const, while the second would be of type TestStruct *const.

Swift also provides closure based APIs to access (and modify) raw bytes of any type. Let’s see how that works.

var test = TestStruct(integer: 42, boolean: true)

withUnsafeMutableBytes(of: &test) { (mutableBufferPointer) in

print(mutableBufferPointer.count) // 5

mutableBufferPointer.forEach { print($0) } // [42, 0, 0, 0, 1]

mutableBufferPointer[1] = 20 // Sets the second byte of integer property in test to 20

}

print(test) // TestStruct(integer: 5162, boolean: true)The pointer type in the closure is UnsafeMutableRawBufferPointer rather than a simple UnsafeMutableRawPointer. This is because a non buffer pointer doesn’t do any bounds checking, meaning you can access bytes outside the scope of test struct using the pointer, which would be confusing. With buffer pointer, the count of the pointer is same as the size it occupies in memory, and bounds checking ensures you get an error if you do something like mutableBufferPointer[10] on a pointer whose count is 5.

There’s withUnsafeBytes as well if you only need to read the bytes. As you’d expect, the pointer we get in the closure has type UnsafeRawBufferPointer.

You might be wondering why 42 - a 4 byte Int32 - is printed as [42, 0, 0, 0] rather than [0, 0, 0, 42]. This has to with endianness. Intel CPUs are little endian, meaning the least significant byte of a multibyte type is stored first.

Pointers and Arrays

In C, array elements are always stored sequentially in memory. This is not true for Swift, where array elements are optimized for storage space. You can verify this by a simple test

var a = [

TestStruct(integer: 15, boolean: true),

TestStruct(integer: 14, boolean: true),

TestStruct(integer: 13, boolean: true)

]

withUnsafePointer(to: a[0]) { (ptr) in

print(ptr) // 0x00007ffeeee6f2b8

}

withUnsafePointer(to: a[1]) { (ptr) in

print(ptr) // 0x00007ffeeee6f2b8

}How come two distinct array elements have the same memory address? Arrays in Swift are not pure value types, but reference types that masquerade as value types. The reason for this warrants a new blog post in itself (look up Copy on Write if you are curious). If you wish to use pointers to arrays, it’s best to use instance methods withUnsafeBytes() and withUnsafeBufferPointer() rather than the global methods.

var a = [

TestStruct(integer: 15, boolean: true),

TestStruct(integer: 14, boolean: true),

TestStruct(integer: 13, boolean: true)

]

a.withUnsafeBufferPointer { (ptr) in

guard let base = ptr.baseAddress else { return }

print(base) // 0x00007fbcb3436010

print(base.pointee) // a[0]

print(base + 1) // 0x00007fbcb3436018

print((base + 1).pointee) // a[1]

}